As stronger alcoholic beverages, such as whiskey, became cheaper due to mass production in the 1800s, more and more Americans began to take up drinking. In turn, more and more Americans became dismayed—especially women who had families.

Women saw a link between their husbands’ drunkenness and the abuse of their finances and, indeed, of their wives. At the time, American women of all races had virtually no legal rights, and those in abusive marriages felt trapped.

Out of this frustration arose Christian, middle-class women who advocated for moderation and later the prohibition of alcohol.

So starting within their social groups, women spread the demand for something to be done until almost all women’s groups knew of and advocated for temperance and moderation.

These women soon realized that the most effective way to achieve victory for their cause was intervention by the federal government. But as there would be no women elected to federal office for decades, it was next to impossible to convince the all-male Congress to support such legislation. In light of this, the women of the temperance movement turned to the suffragists. This would prove to be a rocky road, however, as both groups differed in ideals and viewed each other as extremists for their respective causes.

The two groups finally converged in 1852, when pro-life suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony founded the New York State Women’s Temperance Society. The two women advocated for a woman’s right to vote, temperance, as well as the right for women to divorce drunken husbands. Anthony and Stanton worked to collect 28,000 signatures on a petition for a law to prohibit the sale of alcohol in New York State and organized a hearing before the New York Legislature, the first that had been initiated in that state by a group of women.

At the organization’s convention the following year, however, some traditional members attacked Stanton’s advocacy of the right of a wife of an alcoholic to obtain a divorce. Stanton was voted out as president, and she and Anthony immediately resigned.

The two women traveled throughout New York for the next decade campaigning, and in 1860, they successfully worked to amend New York’s Married Woman’s Property Law, allowing property ownership, suits in court, shared child custody, and the keeping of earnings and inheritance.

In the 1870s, Frances Willard emerged as a leader of the temperance movement and later the suffrage movement. In 1873, Willard was named the first Dean of Women at Northwestern University. The following year, however, she resigned after multiple confrontations with the university’s president, Charles Henry Fowler, over her governance of the Woman’s College. Willard immediately redirected her efforts from education to temperance. She co-founded and later became president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

A very close friend of Anthony, Willard realized the importance of her mission, but more important, she realized the division it had created among women in both the temperance movement and throughout the United States. As the temperance movement began gaining steam within women’s get-togethers and clubs, suffrage was not the primary concern for the WCTU.

Indeed, many women originally disliked the then-radical idea of equal suffrage. Members of this group were concerned with keeping their families together and afloat in an economically challenging time. Willard realized that having the temperance and suffrage movements work together would be more beneficial to both parties and changed the direction of the WCTU to focus on broader women’s issues.

Willard was able to frame women’s suffrage as an essential tool in defense of a woman’s traditional domain of home and family, rather than upending it. Willard was also able to influence the suffragists, urging them to initially gain support on the local level and then work up to something larger, up to and including a federal constitutional amendment.

Allies Divided: Equality Between the Races or the Sexes?

At about the same time as Willard, another woman, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, was paving the way for Black voices in both the temperance and suffrage movements and in other major women’s issues. Although lesser known than Willard both then and today, Harper enjoyed a long writing career and was one of the first Black American women published in the United States, beginning with her first book of poetry in 1845, at just 20 years old. Harper continued to gain notice by publishing in Black journals right after the Civil War.

Harper realized that, as a Black woman, her voice would be drowned out or ignored on her own, so she decided to advocate for women’s rights alongside White women, believing that the attention to be gained would be greater than if she were to approach it separately.

In 1859, she published “The Two Offers” in The Anglo-African newspaper, the first short story to be published by a Black woman. The story highlighted the issues for women regarding the legal statutes and economic dependencies imposed to suppress women.

In 1866, Harper delivered the lecture, “We Are All Bound Up Together,” at the National Women’s Rights Convention, held in New York City, asking White women to take a look at how they, too, might be oppressive to people of color, which stirred up controversy. She based her stance around the idea that the fight to get White women on the voting ballot was only going to serve those of similar status and race. After Harper delivered this speech, the convention agreed to form the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), which incorporated suffrage for Blacks into the broader women’s suffrage movement. The AERA disbanded, however, over strategic disagreements over granting suffrage for all: The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution expanded the franchise to Black men but not women, of any race. Harper supported the amendment and thus fell on the opposite side of Anthony and Stanton, who favored immediate suffrage for all women and men.

In 1869, Harper co-founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) alongside Lucy Stone, who began publishing Woman’s Journal the following year. Frederick Douglass was also a 15th Amendment supporter and collaborated with the organization, which led to a long falling out with Anthony, his dear friend, because he believed it was tactically wiser to enfranchise Black men first, rather than advocate immediate universal suffrage. Compared to Anthony and Stanton’s group, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), Harper’s group also held more traditional stances on marriage and religion, and unlike NWSA, AWSA included men among its members.

Harper also firmly believed that alcohol caused the destruction of families and their homes. Although not as prominent as her work in the suffrage movement, she was a vocal figure throughout the 1880s in lobbying for the WCTU to address Black women’s concerns. She was disappointed, in particular, that Willard gave priority to White women’s concerns, rather than supporting Black women’s goals of gaining federal support for an anti-lynching law, defense of Black rights, or abolition of the convict lease system. Willard, who repeatedly used racially charged rhetoric that played on offensive stereotypes of drunken Black men preying on White women, did eventually relent and explicitly stated her opposition to lynching following an acrimonious exchange with progressive Black journalist Ida B. Wells, in 1893. That same year, Willard successfully urged the WCTU to pass a resolution against lynching.

Temperance and Suffrage Movement Alliances Crumble

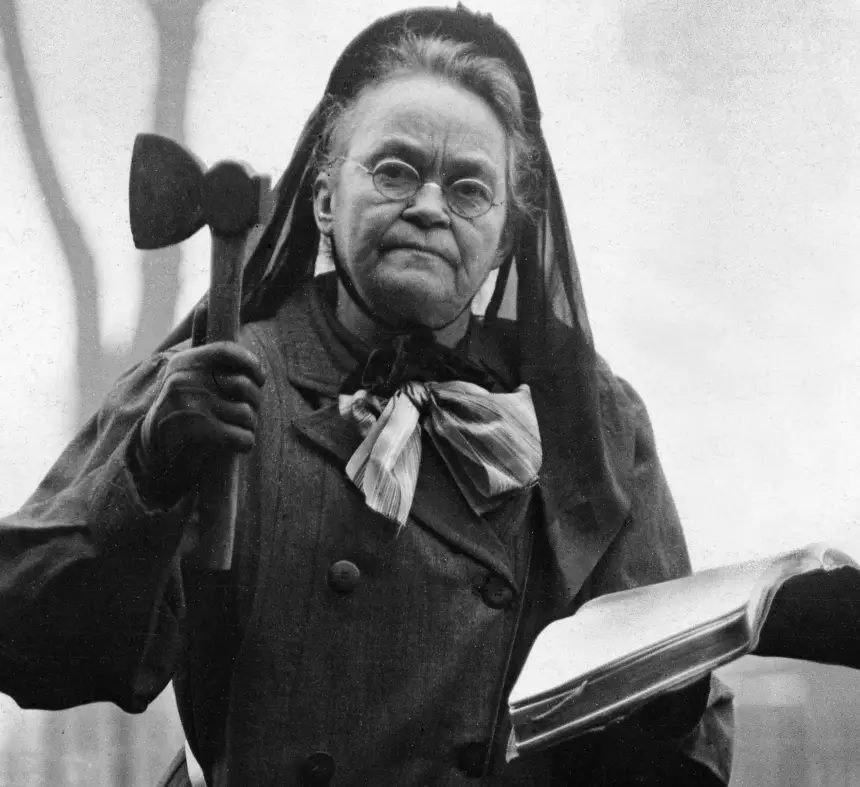

Although the temperance and suffrage movements worked together for several decades, the connection between them crumbled over time. By the end of the 19th century, the movements went their separate ways. After Willard expanded the WCTU’s reach into one too many outlets, many women wanted to focus back on temperance exclusively, and the movement began to lean into more violent methods to get their point across, coming to a head with Carrie Nation, who infamously attacked alcohol-serving establishments with her hatchet.

In 1919, the 18th Amendment, which prohibited alcohol throughout the United States, was ratified; it came into force in 1920. Later that year, a woman’s right to vote was finally protected by the 19th Amendment. Thirteen years later, Prohibition came to an end, following ratification of the 21st Amendment. To date, the 18th Amendment is the only amendment to be repealed by another.

By Katharine Burgess

Sources:

- Temperance and Suffrage – Connected Movements – Suffrage 2020 Illinois

- Temperance & Suffrage | Ken Burns | Not For Ourselves Alone | Ken Burns | PBS

- Abolition, Women’s Rights, and Temperance Movements – Women’s Rights National Historical Park (US National Park Service)

- Women Led the Temperance Charge – Prohibition: An Interactive History

- Willard, Frances E.

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper – First Wave Feminisms (uw.edu)

- Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Suffragist and Advocate for Universal Freedom (newamerica.org)

Quiz