Damian J. Geminder

On March 31, 1776, the effort for women’s suffrage began. The future First Lady Abigail Adams wrote her husband, John Adams, imploring the members of the Continental Congress to “remember the ladies” as they formed a new country:

“I long to hear that you have declared an independency—and by the way, in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

But they were not “remembered,” along with many other groups. When the United States was established, Catholics, Jews, Quakers, and Native Americans could neither vote nor run for official office in some Northern states; white land-owning women in New Jersey and black freemen were able to vote in some areas.

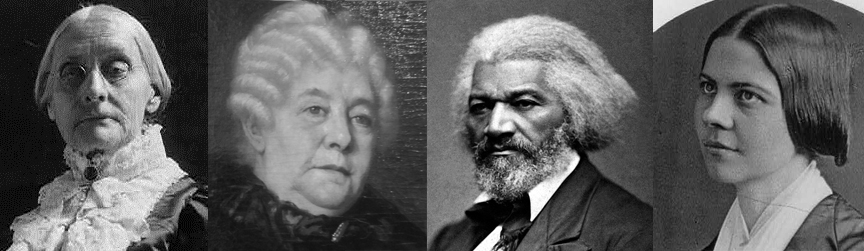

Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, and Lucy Stone founded the American Equal Rights Association for universal suffrage on May 1, 1866 at the end of the 11th National Women’s Rights Convention. Stone was named president. They refused to choose. Sadly, competition for who would have voting rights first—black men or white women— eventually tore the movement in two, while black women found themselves in the middle.

Black men were recognized as citizens in 1870 under the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, though Southern states disenfranchised these new voters by imposing discriminatory poll taxes and literacy tests on them. It took 50 more years for women to win the vote in 1920. Asian Americans were frequently disenfranchised due to targeted anti-immigrant legislation, most notably the Chinese Exclusion Act. Native Americans were finally able to vote after being uniformly granted U.S. citizenship in 1924, but some states continued to discriminate against them for decades. It took until President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 for many African Americans as well as Native Americans to realize their dream as full citizens. A decade later, the Voting Rights Act was expanded to protect “language minorities” from voting discrimination, defined as “persons who are American Indian, Asian American, Alaskan Natives or of Spanish heritage.”

To read more about our Feminist Foremothers, please purchase First Wave Feminists here.