María Adelina Isabel Emilia “Nina” Luna Otero was born on October 23, 1881. Her birthplace near Los Lunas, New Mexico, is about a half hour south of Albuquerque. Nina’s family were well-off, well-educated members of the Hispanos of New Mexico, which was still a U.S. territory at the time. Hispanos are New Mexicans whose ancestry traces back centuries, to the first Hispanic settlers in the region, many of whom lived in what is now the United States decades before Dutch and English settlers colonized the East.

When she was just 2 years old, Nina’s father was killed during a quarrel with a band of Anglos who questioned his property ownership. Her mother remarried three years later. Nina’s mother became director of Santa Fe’s board of education in the early 1900s. Nina’s mother’s activism for social and educational causes inspired her from a young age.

In 1908, Nina married a cavalry officer, Lieutenant Rawson D. Warren, but their union ended in divorce just two years later. To avoid the social stigma of divorce, she told people she was widowed not long after marriage — but kept her husband’s name. Nina Otero-Warren never gave birth, but when her mother died in 1914, she became a surrogate mother to her nine half-siblings.

That same year, Otero-Warren began working with the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (later the National Woman’s Party), which was founded by pro-life suffragist Alice Paul. Otero-Warren rose through the ranks of the state Congressional Union and became its first Mexican-American state leader, at Paul’s personal request. Otero-Warren replied to Paul, “I will keep out of the local fuss… but will take a stand and a firm one whenever necessary for I am with you now and always.” Otero-Warren became a vital liaison to both the Spanish- and English-speaking communities, and although New Mexico did not join its Western neighbors in giving women the vote before it became federal law, Paul credited Otero-Warren’s efforts in ensuring the state voted for passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. New Mexico was the 32nd of 36 states to do so, on February 16, 1920, a day after the centennial of Susan B. Anthony’s birth.

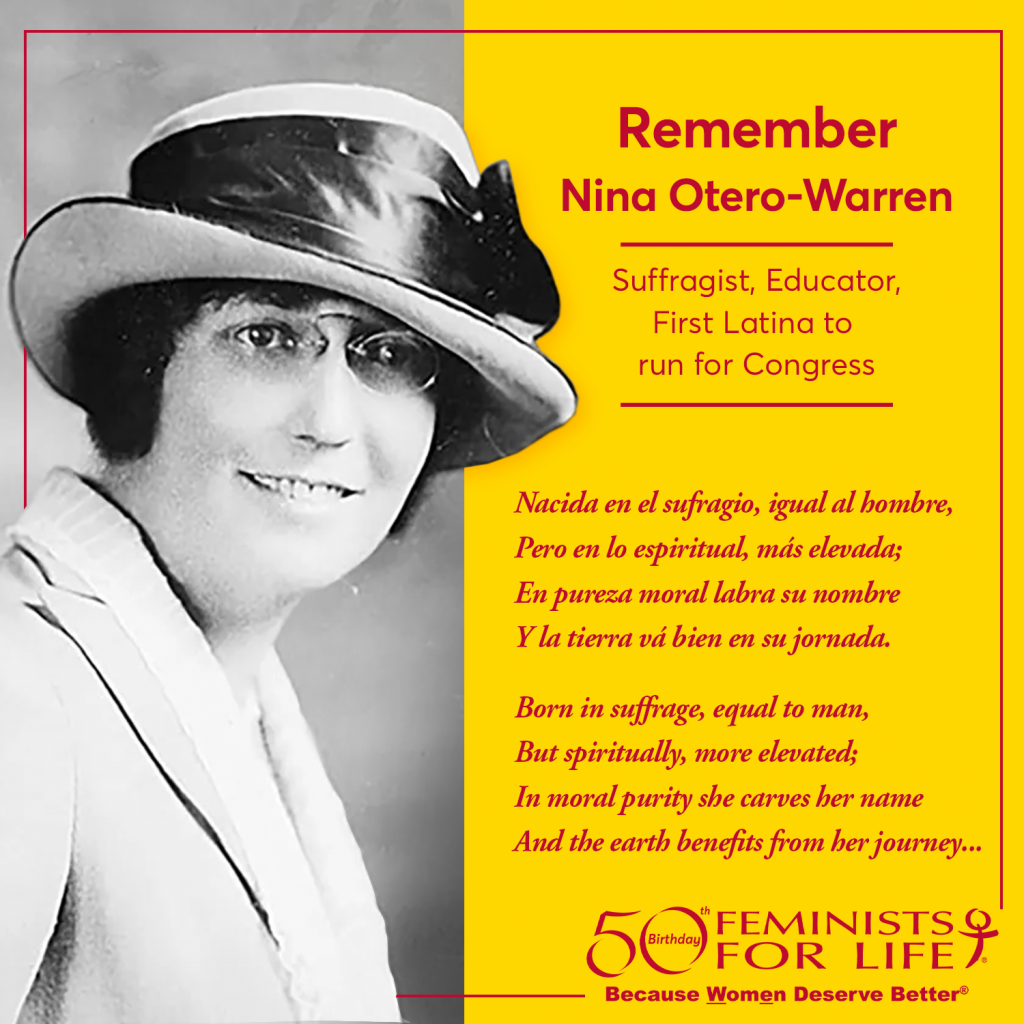

In 1922, Otero-Warren became the first Latina to run for Congress. She ran as a Republican affiliated with the Progressive movement, speaking Spanish during the campaign and advocating for the preservation of Hispanic heritage and culture. As Feminists for Life do today, she also advocated for improved education, health care, and welfare services. The race was highly competitive, because New Mexico, having become a state only a decade earlier, had just one at-large congressional district at the time, making the position highly influential. Ultimately, Otero-Warren lost the race by a margin of just under 10%. It would be another six decades before a Hispanic woman would be sworn into Congress.

Although Otero-Warren failed to win her race, she made history as one of New Mexico’s first female government officials as the Santa Fe Superintendent of Instruction. She was particularly committed to improving educational outcomes for Hispanic, Native, and rural students. At a time when the “Americanization” of Hispanic and Native students all too often meant suppressing their culture and heritage at “best” and outright abusing them at worst, Otero-Warren tried to strike a balance of “Americanization with kindness” that was revolutionary at a time when most Southwestern Spanish-speaking students were punished for speaking their first language. Her curriculum changes included bilingual and bicultural education: “English language instruction in the classroom, teacher sensitivity to different cultures, Spanish instruction through the arts, no punishment for speaking Spanish in the classroom or in the schoolyard, and parent-teacher instruction of artisan trades.” During Otero-Warren’s brief tenure as inspector of Native schools in Santa Fe County, she advocated against sending Native children to boarding schools off of their reservations and sought better cooperation between families and schools. She also sought to integrate opportunities to learn about Native culture, history, and traditions.

Later in life, Otero-Warren continued to promote and celebrate Hispanic and Native cultures, arts, and languages. Her final endeavors included her Santa Fe real estate business, which she began in 1947 and worked at until her death in 1965, at age 83.

Finally, even if you hadn’t heard of Nina Otero-Warren before reading this Herstory profile, you may have seen her recently: on your money! Beginning in 2022, Otero-Warren’s likeness appeared on the reverse side of the U.S. quarter as part of the American Women quarters program. With this, she became the first Hispanic American, of either sex, to appear on U.S. currency.

As we recall Nina Otero-Warren’s legacy, we close quoting from a poem by Hispano poet Felipe Maximiliano Chacón, “A La Señora Adelina Otero-Warren: Candidata Republicana para el Congreso, 1922” (“To Mrs. Adelina Otero-Warren: Republican Candidate for Congress, 1922”). It is one of the first political poems, popular among the Spanish-language newspapers, recognizing a Hispana politician:

Nacida en el sufragio, igual al hombre,

Pero en lo espiritual, más elevada;

En pureza moral labra su nombre

Y la tierra vá bien en su jornada.

Aquesta evolución tan meritoria,

Marcando el alto paso del Progreso,

Cubrirá Nuevo México de gloria

Poniendo una mujer en el Congreso…

Born in suffrage, equal to man,

But spiritually, more elevated;

In moral purity she carves her name

And the earth benefits from her journey.

This very meritorious evolution,

Marking the noble path of Progress,

Will cover New Mexico with glory

By putting a woman in Congress…

By Editor Damian J. Geminder