Sophia Duleep Singh was a typical British suffragette, blending in with the crowds of protestors; her only stated interest was “the advancement of women.” But Sophia’s life was anything but typical.

Sophia’s story begins four thousand miles away from her home, with her grandfather Ranjit.

Ranjit Singh was the only ruler of the Sikh Empire, located in Punjab, in what is now Pakistan and northwest India. When the British annexed the area in 1849 after two wars, his five-year-old son, Duleep Singh, was kidnapped and later exiled to Britain. Duleep was completely anglicized in his new environment, therefore preventing any future Punjab resistance. He became close friends with Queen Victoria, and she made sure he lived comfortably for the rest of his life.

Born in 1876, Sophia was the fifth child of Duleep and Bamba Muller, who was the illegitimate child of a German merchant and an Ethiopian slave. Despite having such diverse lineage, Sophia was raised as a completely English child, with a very aristocratic upbringing. She never received formal education, instead spending her time breeding show dogs and buying dresses from Paris. Sophia began to be noticed in England for her fashion sense and posh lifestyle. She was as close to an international celebrity as it was possible to be in 1910. As with many of Duleep’s children, Queen Victoria was her godmother. When Sophia came of age in 1894, the Queen gifted her a “grace-and-favour” apartment, where she lived for most of her life.

This type of lavish existence was not uncommon at the time, but Sophia’s life took a different turn after she made several trips to colonized India in the early 1900s. During her second trip in 1907, she visited several major cities and was struck by the poverty of colonized India. Sophia also met with freedom fighters such as Lala Lajpat Rai, who had been imprisoned under charges of sedition. These experiences politically radicalized her, turning her against the British Empire she had lived under her whole life. Sophia began to take much more interest in politics and human rights issues after these trips.

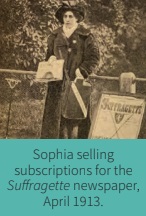

Back in England, Sophia joined the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1909. She donated money and time, quickly becoming more noticed in feminist circles due to her celebrity and official title of “Princess.” Sophia sold suffragist newspapers outside of Hampton Court Palace, where Queen Victoria had allowed her to live. Though the Queen was dead and Sophia was increasingly provoking the government, she was never evicted from her home.

On November 18, 1910, Sophia and many other leading suffragists went to the House of Commons, demanding to speak to the Prime Minister. When police cleared the area, many suffragists were seriously injured and arrested. This day became known as Black Friday. While Sophia was arrested along with her friends, she was treated much more kindly due to her high-profile status.

Sophia also refused to pay taxes to a government that did not represent her. When questioned in court she answered, “I am unable conscientiously to pay money to the state, as I am not allowed to exercise any control over its expenditure, neither am I allowed any voice in the choosing of members of Parliament. This is very unjustified.” Although Sophia was repeatedly brought back to court and charged further fines, she steadfastly refused to pay. When the police seized some of her possessions, including jewelry, other suffragists bought them back at an auction and returned them to her.

After census papers arrived at Sophia’s home in 1911, she joined other suffragists in refusing to complete the forms. At the bottom of the page, she wrote the anti census slogan, “As women do not count, they refuse to be counted.” While this of course further frustrated the government, neither Sophia nor other women who did the same were prosecuted.

Although leaders in the movement wanted to harness Sophia’s status for publicity, she was a very shy woman and wanted to avoid attention as much as possible, describing herself as “quite useless for that sort of thing.” She preferred to blend in with the rest of the movement, instead of promoting her celebrity status. Sophia’s wealth was also advantageous for the cause; she assisted with funds and on several occasions posted bail for fellow suffragists.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Sophia volunteered as a Red Cross nurse, mainly assisting Indian soldiers who were fighting on behalf of Britain. Soldiers from Punjab were in awe at meeting the granddaughter of their legendary king. Back at home, she organized fundraising efforts for the men on the front, particularly a large event called “India Day” which was a huge success.

In February 1918, the Representation of the People Act granted women over 30 the right to vote. While this was a major victory for the suffrage movement, the next several years were troubling for Sophia. Her siblings drifted apart, the political and social situation in India was getting worse, and it was becoming increasingly hard to make ends meet. However, there were also flashes of good news. In 1928, the British government extended suffrage to all women over 21. Sophia’s mission of womens’ suffrage was complete, and she led a relatively quiet life until her death in 1948.

Sophia Singh was a unique and revolutionary woman for her time, breaking the molds of strict Victorian society. She was ethnically Indian, but a thoroughly British aristocratic woman. She held the title of Princess, but joined an anti-government movement. She was sophisticated, but devoted herself to a controversial and often messy social cause. Sophia defined her own life and legacy, never listening to what or whom society said a woman like her should be.

By Stella Masucci

Editor’s Note: Unlike American suffragists, their British counterparts embraced the slur “suffragette” as their own.

To read more about our Feminist Foremothers, please purchase First Wave Feminists here.