Frederick Douglass: Suffragist. Abolitionist. Ally.

Abolitionist and suffragist Frederick Douglass was born into slavery to a mixed-race mother and a White father on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Talbot County, Maryland, in February of 1818. Although no official record of his birthday exists, it is commonly attributed to Valentine’s Day, because his mother called him her “little valentine.”

Douglass fell in love with Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore, in 1837. She provided him with aid and money, eventually helping him attain his freedom in 1838. Douglass wound his way north by train and ferry, from Maryland, through Delaware, and finally to the free state of Pennsylvania. Murray provided him with a sailor’s uniform to wear as a disguise, in addition to giving him part of her savings to cover his travel costs. He also carried identification papers and protection papers that he had obtained from a free Black seaman. The entire journey took less than 24 hours.

Just 11 days after Douglass’ successful escape, he and Murray married. They had five children together and remained married until her death in 1882.

Douglass Finds His Voice

Shortly after their wedding, the Douglasses settled in Massachusetts. There, Frederick Douglass became a licensed preacher and honed his oratorical skills. He joined several organizations in New Bedford — an abolitionist center full of former slaves — and regularly attended abolitionist meetings.

Douglass was particularly inspired by abolitionist and suffragist William Lloyd Garrison and subscribed to his weekly newspaper, The Liberator. Garrison was likewise impressed by Douglass. Eventually, Douglass became an anti-slavery lecturer and conquered his nervousness to discuss his life as a slave. He lectured across the country and eventually made his way to Ireland and Great Britain, where he lived and toured from 1845 to 1847.*

Upon his return to the United States, Douglass started publishing his first abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, from a church basement in Rochester, New York. The publication’s motto was, “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.”

Frederick Douglass the Suffragist

In 1840, abolitionists convened in London for the World Anti-Slavery Convention. What should have been a uniting cause in support of freedom, sadly, became one of division over another form of discrimination. Male organizers ruled that women could attend the convention but not speak. American abolitionists Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton met there and decided to collaborate. Eight years later, they organized the Seneca Falls Convention.

The event was particularly momentous: It was the first-ever women’s rights convention. Stanton, considered the Mother of the Women’s Movement, was the principal author of the Declaration of Sentiments, a document largely based on the Declaration of Independence but also intended to be the “grand movement for attaining the civil, social, political, and religious rights of women,” as reported by The North Star.

Although the convention’s attendees were generally in agreement about the rights of women, it was suffrage itself that proved most divisive. Even Mott herself urged removing the concept out of fear that it was too radical for the time. But it was none other than Douglass himself who swayed those assembled in favor.

Douglass, the only African-American of either sex in attendance, declared that he could not accept the right to vote himself as a Black man if women could not also claim that right: “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

The resolution passed by a large majority. Douglass would go on to be the sole Black signatory of the Declaration of Sentiments.

Douglass and Lincoln: Foes to Allies to Friends

June 19, 1865 marked the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas, the final and most geographically remote of the former Confederate states to surrender and free its slaves. Feminists for Life of America has remembered this historic day, now called Juneteenth, since before it became a federal holiday in 2022.

President Abraham Lincoln, who had been assassinated two months prior, relied on Douglass for counsel on racial issues during the U.S. Civil War. In 1863, they conferred on the treatment of Black soldiers and plans to move liberated slaves out of the South. Douglass did not support Lincoln’s reelection, however, because he failed to publicly support suffrage for Black freedmen. If Black men could fight for the Union, Douglass argued, they deserved the right to vote.

Lincoln did win, of course, and Douglass met with him once more. According to The White House Historical Association:

“After President Lincoln’s second inauguration in 1865, Douglass met with him for the last time. Douglass made the trip to Washington, D.C. to hear the president’s speech, and later attempted to visit him at the White House. White doorkeepers initially barred his entrance, based solely upon his race. However, Douglass negotiated his way into the East Room, where he was happily received by his foe-turned-friend. There, Lincoln said, ‘I am glad to see you. I saw you in the crowd to-day, listening to my inaugural address…Douglass; there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you think of it.’ This meeting, where a formerly-enslaved man was greeted by the American president as a ‘man among men,’ resonated with Douglass for the rest of his life.

“Less than two months later, President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth during a trip to Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Following his death, First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln sent Douglass her husband’s ‘favorite walking staff’ in recognition of the relationship between the two men, and the impact that Douglass’s advice had had on the president.”

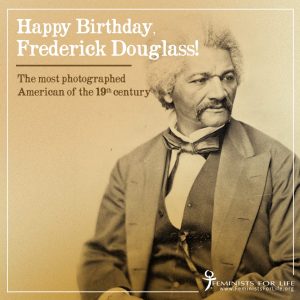

The Most Photographed Man of the 19th Century

Douglass is widely considered to be the most photographed American of the 19th century. There are 160 known photographs of Douglass, from just after he escaped from slavery in Maryland in 1838, to his deathbed in 1895. President Lincoln, meanwhile, has a comparably paltry 126 recorded photographs.

At a time when Black Americans were frequently depicted using the most offensive of racist imagery, most infamously in minstrel shows, Douglass felt obligated to present an honest portrayal of his race. Photography was still revolutionary technology, and with the photo editing software we now take for granted decades away, Douglass observed that it was a far more objective art form than others: “Negroes can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists. It seems to us next to impossible for white men to take likenesses of black men, without most grossly exaggerating their distinctive features.”

Douglass also noted that unlike a professionally commissioned portrait, a photograph was widely accessible to the public, regardless of race or class: “The humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself such as the wealth of kings could not purchase fifty years ago.” Frederick Douglass was a man who knew that our beauty as humans came from inside. Ever the pragmatist, however, he knew that many people would need to see him and his peers’ beauty on the outside first.

Feminist Friendships Frayed

In 1866, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony founded the American Equal Rights Association. Both Black and White suffragists were members, most famously Stanton, Anthony, and Douglass. AERA’s constitution stated that they “worked to secure equal rights to all American citizens, especially the rights of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex.”

Following the Civil War, three amendments related to the rights of Black Americans were ratified. The 15th Amendment, which granted suffrage based on race but not sex (more often in theory than in practice), caused a great rift between Douglass and White female suffragists, not because of intent but because of strategy.

Douglass believed that Black men should get the vote first and then women of all races could be enfranchised after. Anthony, a supporter of universal suffrage, was hurt and furious. “I would rather cut off my right arm than lift two fingers to help Black men get the vote first,” she said.

This quote, sadly, is taken out of context by some today, who ignore that Anthony wanted Black men and women to gain the franchise simultaneously with White women. Indeed, the suffragists were so committed to ending slavery that they stopped their activism for women’s suffrage during the Civil War.

After the 15th Amendment’s ratification in 1870, however, Douglass and Anthony reconciled and reunited in support of women’s suffrage.

In 1872, abolitionist, suffragist, and anti-abortion advocate Victoria Woodhull became the first woman nominated for President of the United States. Douglass likewise made history as the first Black American ever nominated for Vice President — although he was nominated without his knowledge and never campaigned.

Love Beyond Prejudice

In 1884, two years after his beloved Anna’s death, Douglass married again: this time, to Helen Pitts, who was not only 20 years his junior but White as well. At a time when interracial marriage was outlawed throughout most of the United States, the union was incredibly controversial. Even Helen’s own parents, who were themselves abolitionists, were opposed, and Douglass’ children viewed the marriage as a repudiation of their mother. But the two were resolute in their love, with Helen saying, “Love came to me, and I was not afraid to marry the man I loved because of his color,” and Frederick quipping, “This proves I am impartial. My first wife was the color of my mother and the second, the color of my father.”

It was none other than Elizabeth Cady Stanton herself who vocally defended the marriage: “In defense of the right to… marry whom we please — we might quote some of the basic principles of our government [and] suggest that in some things individual rights to tastes should control…. If a good man from Maryland sees fit to marry a disenfranchised woman from New York, there should be no legal impediments to the union.”

The wedding was officiated by Rev. Francis James Grimké, a Presbyterian minister in Washington D.C., one of the few jurisdictions where interracial marriage was legal at the time. The day was particularly meaningful: Like Douglass, Grimké was also born into slavery to a mixed-race mother and a White father. Grimké’s niece, journalist, poet, and playwright Angelina Weld Grimké, would go on to be one of the most prominent suffragists of color of the 20th century and an outspoken opponent of abortion.

Douglass’ Final Days

In 1877, Douglass bought what would become his family’s final home in Washington D.C. He was tireless throughout the final two decades of his life. In 1881, he published the final edition of his autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass — and then he updated it in 1892. Douglass served in multiple local and public appointed positions and continued to lecture domestically and abroad.

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. There, he was invited by the White suffrage leadership to join them on the dais, and he asked Anthony to escort him. That night, he was extremely excited as he told his wife about the day, and he suddenly fell unconscious, having suffered a massive heart attack. According to The New York Times, Anthony was visibly upset upon learning that her friend had passed.

Anna Murray, Helen Pitts, and Frederick Douglass’ remains are now buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York. His friend Susan B. Anthony was laid to rest at the same cemetery.

By Damian Geminder

*Indeed, Douglass’ legacy lives on in the Emerald Isle to this day: His likeness is the centerpiece of one of the famous wall murals in Belfast, Northern Ireland, along with other Black American figures. The symbolism of Douglass is twofold: Just as the United States was riven by war between North and South over slavery, so too was Ireland the site of the bloody Troubles conflict between Protestant unionists and Catholic nationalists. Additionally, many Irish Catholics in the 19th century viewed their oppression under British rule as analogous to that of Black Americans under slavery.

Read More: