By 1912, the women’s suffrage movement had long been underway. Sixty-four years had passed since the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York. While women’s suffrage conventions were held routinely during those six decades, suffragists had yet to persuade the general public to take up their cause. Between 1912 and 1919, however, suffragists employed new tactics to reach voters, including suffrage restaurants, automobile tours, train tours, and even airplane pamphlet drops—on the President. Here are just a few of their stories.

Where is a woman’s place? Is it in the voting box or is it in the kitchen?

A Foot in the (Kitchen) Door

Where is a woman’s place? Is it in the voting box or is it in the kitchen? In the minds of many who opposed suffrage, the two were mutually exclusive, and the latter was an absolute truth. People often accused suffragists of having abandoned all traditional responsibilities in order to campaign for voting rights.

To fight these accusations, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont opened “The Suffrage Cafeteria” in Brooklyn in 1912. In the years prior, the suffrage movement had used teas and luncheons in their fundraising efforts. Belmont’s kitchens—she ultimately opened about 11 in Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Long Island—took a different approach. They served cheap but high-quality meals to customers—on china painted with suffrage slogans.

This was no fundraiser tea. This was a suffragist mission, and its targets were the men, the ones who held power to vote.

As one suffragist who worked at the cafeteria said, “We lured men in, for a good, cheap business lunch. Then you could hand them literature and talk.”

There was no escaping the message when it was looking up at you from your plate.

The genius of these restaurants was not just the combination of low prices and creative dishware. By opening the kitchen door and turning the traditional woman’s place in the kitchen into an entrepreneurial and activist enterprise, Belmont’s kitchens were examples of how women used equal ability to actively contribute to society in different ways. Belmont’s newfound capacities as restaurant owner, manager, and head waitress were no less womanly than any traditional role, silencing any criticism of her womanhood.

Suffrage Road Trips

The same year Belmont entered the New York City restaurant scene, “General” Rosalie Jones left New York City with a band of suffrage pilgrims. She marched through 150 miles of December weather to Albany and then continued on to Washington D.C. via horse-drawn carriage and automobile, ending with the National Woman Suffrage Parade on March 3, 1913. This long pilgrimage, earning Rosalie Jones her title as “General,” was just the beginning of a series of suffrage road trips. In 1913, a delegation of 48 NAWSA (National American Woman Suffrage Association) suffragists drove west across the country to collect petition signatures. They reconvened at Hyattsville, Maryland on July 31, 1913, to complete the last leg of the auto tour and to present the petitions in Washington D.C.

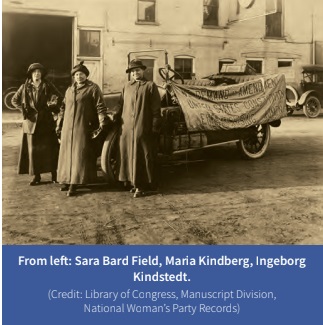

In 1915, Sara Bard Field and Frances Jolliffe drove a massive 18,000-foot-long petition carrying half a million signatures from the Women’s Voters Convention in San Francisco to Washington D.C. The act of taking such a road trip in itself defied the status quo as the women drove without male chaperones. At the time, the American road network was far from complete, and such a long journey required regular car maintenance, of which women were not deemed capable. Along the way, the women spoke about suffrage to the people they encountered. When Jolliffe became ill and could not continue, Field was accompanied by Maria Kindberg and Ingeborg Kindstedt for the remainder of the 5,000-mile journey eastward to deliver the petition to President Woodrow Wilson.

Burke published diary entries in the New-York Tribune documenting their travels (one-time describing driving on a road half planted with potatoes) and the ways they were welcomed in the towns they visited.

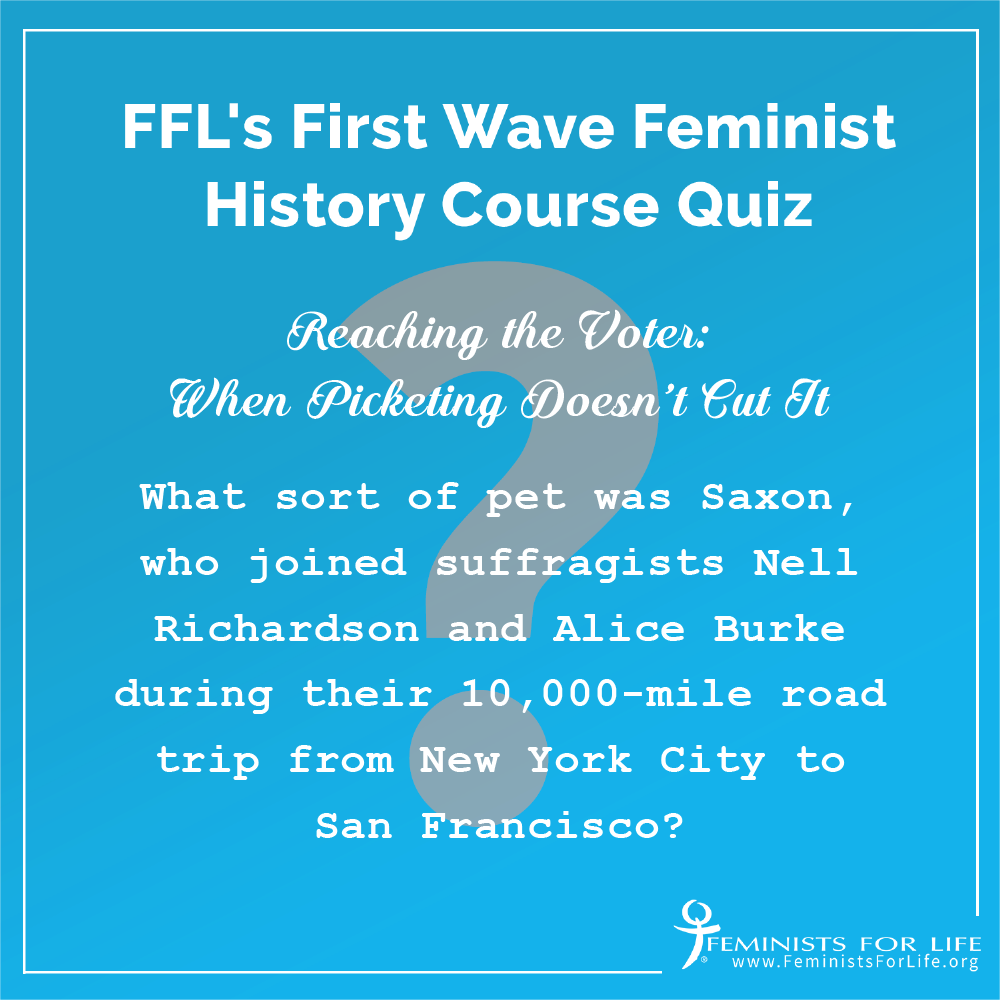

In 1916, Nell Richardson, Alice Burke, and Saxon— their cat—drove “The Golden Flier” from New York City to San Francisco. Saxon, a black kitten, was given to them 20 days into the 10,000-mile journey and traveled with them all the way to San Francisco. Burke published diary entries in the New-York Tribune documenting their travels (one time describing driving on a road half planted with potatoes) and the ways they were welcomed in the towns they visited. The pair and their cat thus acquired a following, as readers of the paper were, in a way, invited to come along for the ride for suffrage.

Suffrage Takes Flight

At a 1913 Staten Island aviation festival, General Rosalie Jones flew over crowds in a Wright biplane piloted by Harry Bingham Brown. They dropped suffrage pamphlets and upon landing, Jones addressed the crowds and then released 100 multi-colored balloons.

The New York Times described her demeanor at takeoff:

Gen. Rosalie did not show a sign of fear as she took her seat in the bi-plane, seized a steel rod, the only thing to hold to, with her left hand, had her skirts tied down with a little piece of blue string, and, with a bunch of yellow Votes-for-Women leaflets in her right hand, nodded a smiling good bye to the crowd below.

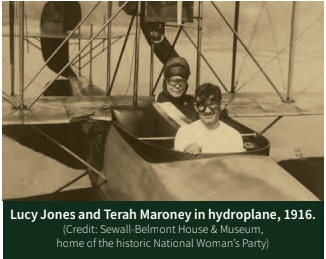

Suffrage took flight again in 1916, when Lucy Jones and Terah Tom Maroney flew over Seattle dropping pamphlets publicizing the upcoming National Woman’s Party Convention in Chicago.

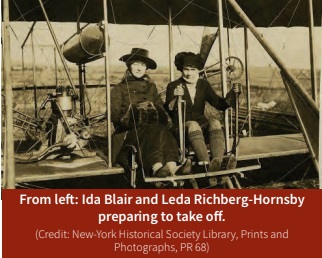

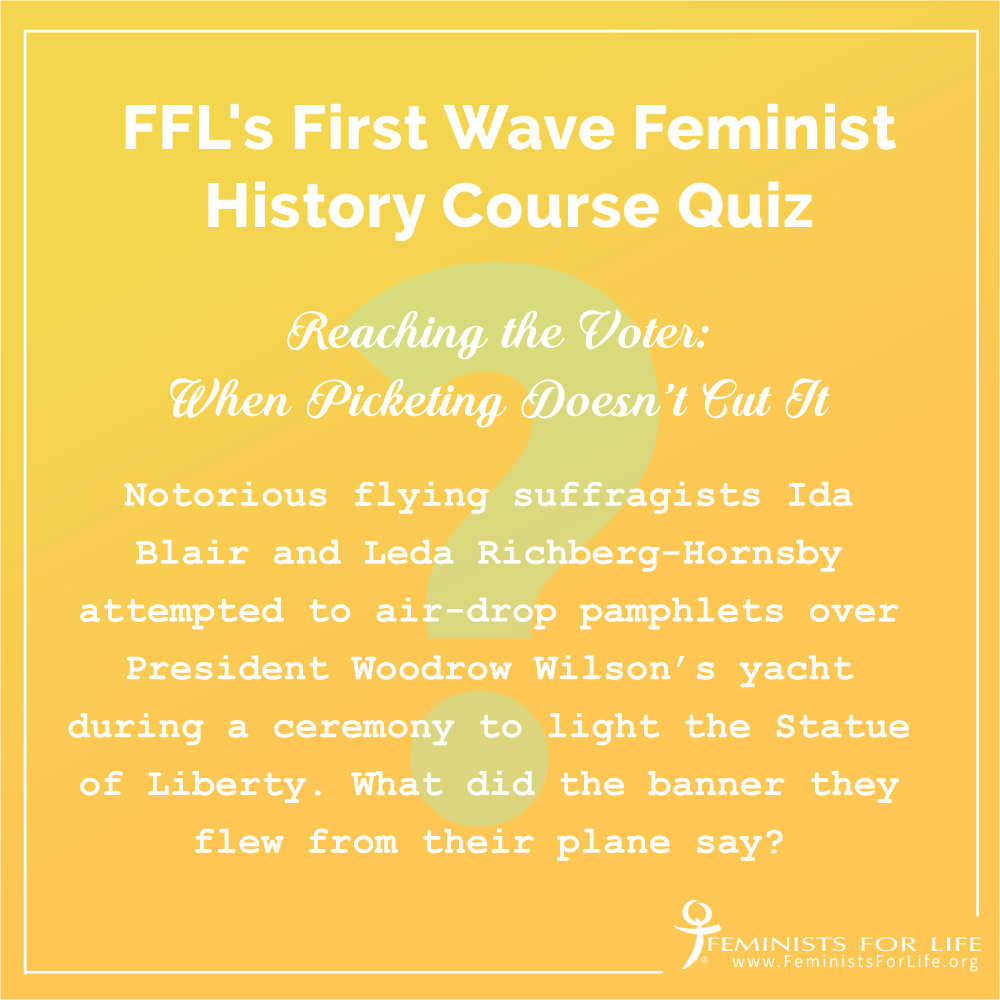

The most notorious flying suffragists were probably Ida Blair and pilot Leda Richberg Hornsby. Richberg-Hornsby was the first female graduate of the Wright School of Aviation in Dayton. The two attempted to drop pamphlets over President Wilson’s yacht during a ceremony to light the Statue of Liberty, only to be forced to land due to high winds. The plane was decorated with streamers of yellow, white, and blue—the suffrage campaign colors—and a banner reading “Women Want Liberty Too.”

Suffrage on the Rails

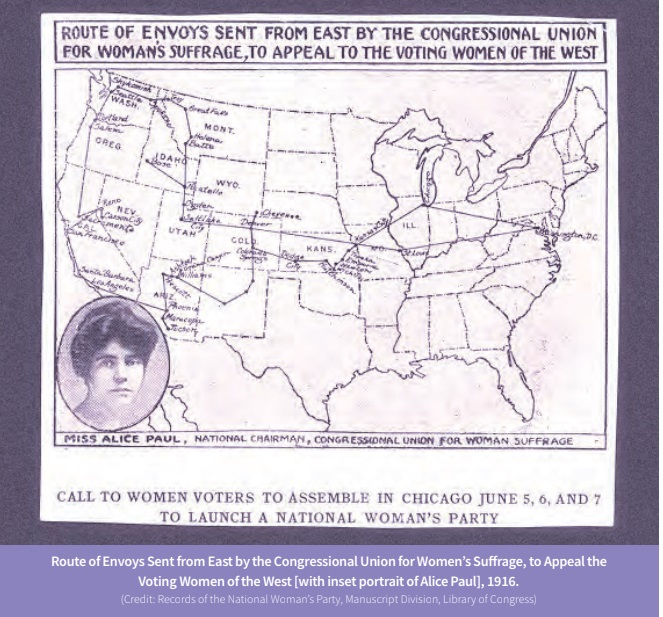

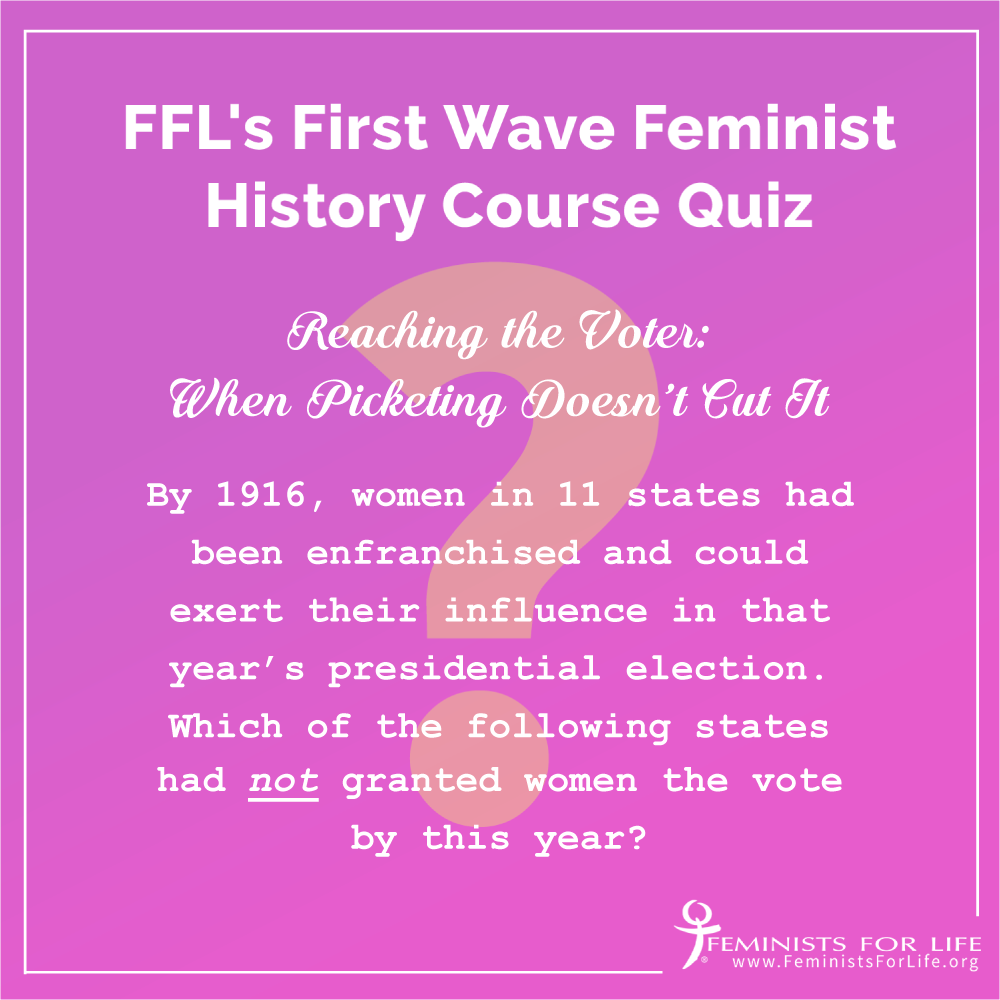

By 1916, 11 states—Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming—had ratified amendments giving women the right to vote. This placed a whole new target demographic—women voters—in the crosshairs of suffragists, who aimed to influence that year’s presidential election.

To get these voters on board, 23 members of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage left Washington D.C. in April 1916 aboard the “Suffrage Special.”

They headed west, traveling and speaking to voters for a total of five weeks. When they returned to D.C. in May, they led an automobile procession from Union Station to Congress to present their petition.

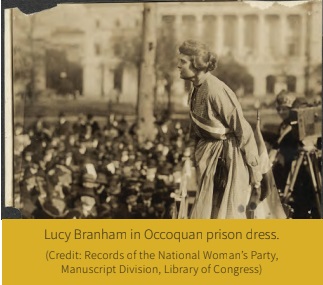

The next time the suffragists staged a railway campaign was 1919. The “Prison Special” tour focused on telling the stories of the suffragists who were arrested and imprisoned for picketing the White House. In prison, many experienced violence, intimidation, unsanitary living conditions, and solitary confinement. During the famous suffragist hunger strike, the women endured painful force-feeding. From June to November 1917, 168 women were imprisoned; most of them were released in November due to pressure from the public.

The train “Democracy Limited” carried 26 NAWSA representatives for three weeks in February 1919. They traveled in their prison uniforms and addressed crowds, which were not always receptive. The women were assaulted by angry crowds on more than one occasion. The tour did the trick, though, generating controversy and stirring up the people who heard them speak. A year later, the 19th Amendment was ratified and adopted nationwide.

Proving the Effect of “Woman’s Hand”

In myriad ways, from cooking, to driving, to flying a plane, these women employed novel techniques to reach voters where they were. By passionate word and deed, they showed the world that woman is equal to man in her ability to contribute to society and in her right to a say in how she is governed. They showed the world, as one Alabama onlooker remarked as Alice Burke skillfully replaced spark plugs, “that ‘woman’s hand in the machinery of politics might have the same helpful effect.’”

By Annmarie Y. Arnold

FFL’s First Wave Feminist Course Quiz

Learn more about Alice Paul:

To read more about our Feminist Foremothers, please purchase First Wave Feminists here.