Pro-life women have often been stereotyped as blindly submissive to patriarchal ideological rule. How, then, to explain Matilda Joslyn Gage? Because her contemporaries — even other feminists — found her uncomfortably radical, Gage has been largely forgotten even in the field of women’s studies, which she trailblazed. Yet there is so much to learn from the life and work of this richly gifted, passionately committed foremother.

She grew up in a stimulating, affirming environment unknown to most 19th-century girls. Her parents valued her education, formal and informal, as much as that of a son. Their upstate New York home, a gathering place for thinkers and activists, was a station on the Underground Railroad. From her physician father she inherited the passion to heal, and from her mother a love of antiquarian books and old histories. According to The History of Women’s Suffrage, she fervently believed “the grandest training given her was to think for herself.”

Gage was barred from medicine, her chosen profession, because she was female. She then practiced the healing art of feminist scholarship and activism, even as she raised a family, struggled with recurrent ill health, and faced derision as the lone radical in her small town. From the beginning, she grounded her efforts in her painstaking, creative research and reclamation of women’s largely overlooked history. At the 1852 Syracuse women’s rights convention, the 25- year-old Gage, who knew none of the leaders, bravely rose and delivered a speech about women’s already impressive record of historical accomplishments, so often suppressed or usurped by men. The speech was immediately reprinted and distributed as part of the official movement literature.

As editor of the suffragist paper National Citizen and Ballot Box,co-editor of the monumental The History of Women’s Suffrage, and a writer herself, Gage further challenged patriarchal culture’s outright robbery of women. She took on issues that many hesitated to face — prostitution, the “common woman’s” abysmal working conditions, the “justice” system’s inadequate prosecution of rapists and the U.S. government’s cruelty toward Native Americans. The contrast between the U.S. government and the egalitarianism of the Iroquois nation helped shape her view that government does not create human rights; it either honors or violates the rights naturally gifted to us by “the Divine.” Gage felt the American Centennial celebration and the 1886 unveiling of the Statue of Liberty were travesties. She created imaginative and even civilly disobedient — though wholly nonviolent — responses to these events. She also staged events in support of Susan B. Anthony’s illegal attempt to vote.

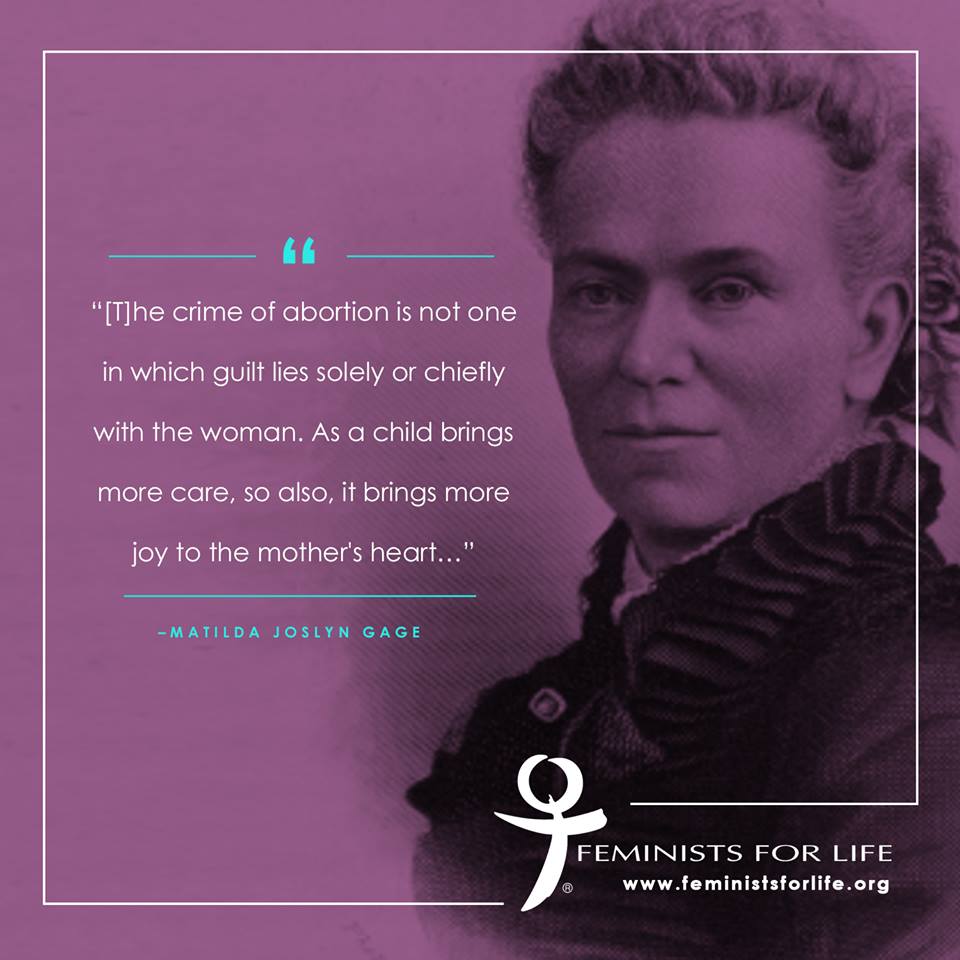

Gage clearly believed that both abortion and the failure to hold coercive men in any way responsible for it were products of a patriarchal legacy. Her Centennial “Declaration of Rights of Women of the United States” asserted a “right to trial by a jury of one’s peers:” “Young girls have been arraigned in our courts for the crime of infanticide; tried, convicted, hung — victims, perchance, of judge, jurors, advocates — while no woman’s voice could be heard in their defense.” Women were not permitted to sit on juries at the time. An earlier piece by Gage in the radical women’s paper The Revolution unambiguously shows that her term “infanticide” includes child killing before and after birth. She insists that the “spiritual origin” of this oppression be recognized: “History is full of wrongs done the wife by legal robbery on the part of the husband…. I hesitate not to assert that most of this crime of child murder, abortion, infanticide, lies at the door of the male sex.” She then states that a woman merits trial by a jury of her peers in such cases of “crimes committed against her as a woman.”

In the spirit of her life and work, let us restore Gage to her rightful place in history. She can inspire us in the very task that brings us to pro-life feminism and keeps us there: thinking for ourselves so that we can act to bring about liberty and justice for all, not some.

Mary Krane Derr

Reprinted from The American Feminist, Winter 1997-98

Mary Krane Derr is co-editor of the anthology Pro-Life Feminism, Yesterday and Today.