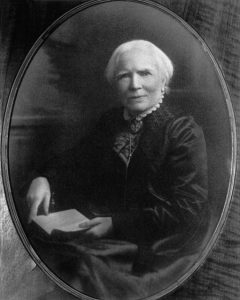

In 1849, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910) became the first woman to receive a medical degree from an American medical school, and in 1859 became the first woman on the British medical register. She was ardently anti-abortion and pro-woman, choosing to enter the field of medicine partly because she was repulsed that the term “female physician” was applied to abortionists.

Born in Bristol, England, Blackwell moved with her family to the United States at the age of eleven. The Blackwell family was very active in the movements to abolish slavery and enfranchise women; Elizabeth’s sisters-in-law included suffragists Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell, and she was a friend to abolitionist novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Initially repulsed by the idea, more than one event contributed to Blackwell’s entering the medical profession. “The idea of winning a doctor’s degree,” she wrote, “gradually assumed the aspect of a great moral struggle, and the moral fight possessed an immense attraction for me.”

The idea was suggested, for example, by a friend dying of cancer, who told her “If I could have been treated by a lady doctor, my worst sufferings would have been spared me” and recommended that Blackwell devote her intellect and love of study to the service of suffering women. “Why don’t you study medicine?” her friend asked.

Related concerns eventually convinced Blackwell. Struck by an article in the New York Herald about Madame Restell, a woman notorious for selling abortifacient medicines and performing surgical abortions, Blackwell wrote in her diary:

The gross perversion and destruction of motherhood by the abortionist filled me with indignation, and awakened active antagonism. That the honorable term ‘female physician’ should be exclusively applied to those women who carried on this shocking trade seemed to me a horror. It was an utter degradation of what might and should become a noble position for women…. I finally determined to do what I could do ‘to redeem the hells,’ and especially the one form of hell thus forced upon my notice.

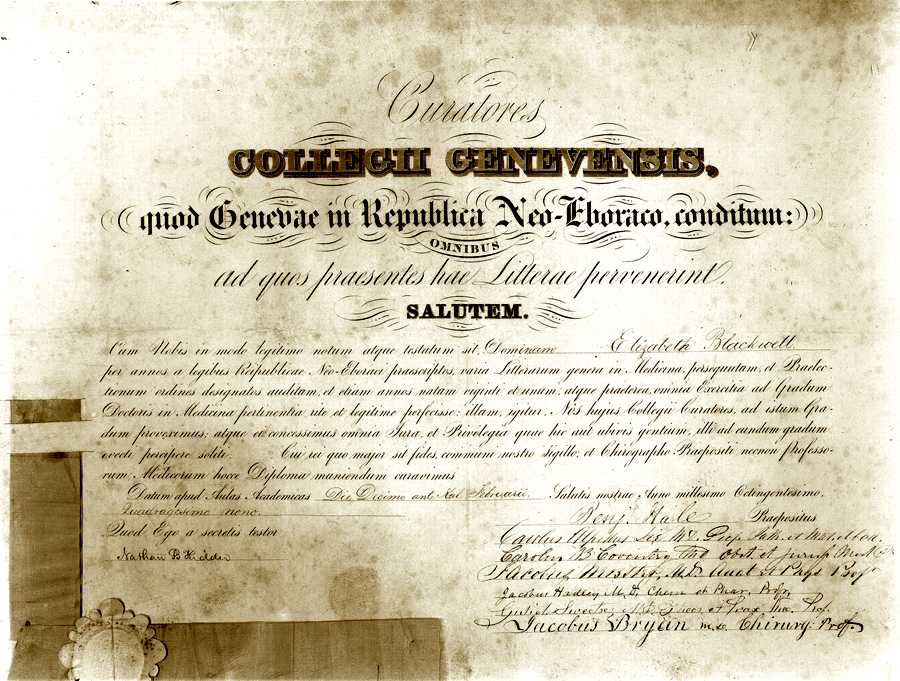

The fact that other people considered her medical education impossible only spurred Blackwell on. She read medical texts with physician friends and applied to several medical schools. She was eventually accepted by Geneva Medical College in New York in 1847; anecdotal evidence suggests that the male students may have voted in favor of her admission as a joke. Blackwell graduated at the top of her class. After gaining more practical experience in clinics and studying midwifery in Paris and London, where she met Florence Nightingale, Blackwell returned to the United States, where in 1857 she incorporated her dispensary as the New York Infirmary for Women and Children with her sister Emily — America’s second female physician — and their friend Dr. Marie Zakrzewska. The Infirmary was the first American hospital staffed by women, providing medical training and experience for women doctors as well as care for the poor. Blackwell later opened a women’s medical college at the hospital, based on a plan developed with Nightingale.

In 1869, Blackwell returned to England permanently, where she established a private practice, helped organize the National Health Society, and became professor of gynecology at the London School of Medicine for Women.

By Cat Clark

References:

- Prolife Feminism Yesterday and Today, Mary Krane Derr, Rachel Macnair, Linda Naranjo-Huebl, eds.

- Encyclopedia Britannica Profiles 300 Women Who Changed the World, (http://search.eb.com/women/article-9015561).

- National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women’s Health, National Library of Medicine, ‘Celebrating America’s Women Physicians’ (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/changingthefaceofmedicine/physicians/biography_35.html).

- Child of Destiny: The Life Story of the First Woman Doctor, Ishbell Ross, (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1949), p. 88.

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges website: http://campus.hws.edu/his/blackwell