The prevailing “wisdom” of her day decreed that females were weak, incompetent, incapable of making valuable contributions to the common good. But Charlotte Denman Lozier never believed it. When she was very young, her family left their hometown of Milburn, N.J., for the then frontier area of Winona, Minn. After losing her mother in her early teens, she supported her younger siblings by teaching. At age 20 she returned East not for a softer life, but to earn a degree at the New York City Medical College for Women, an institution deemed outrageous not only because the students were female, but because they were taught about hygiene and patient self-help. While a student, she organized a successful protest against Bellevue Hospital’s refusal to extend clinical privileges to medical women. Upon graduation, she gained a professorship in the college. She married the physician son of college founder Clemence Lozier, a remarkable woman in her own right. Charlotte proceeded to bear and raise several children while teaching and maintaining an active maternal/child health practice.

Yet she was not content to keep success to herself. Countering the ugly stereotypes of subversive females, Cyrus Foss, her pastor at Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church, remarked: “She was no an unwomanly woman without a heart, nor with possibilities of affection utterly subordinated to ambition or pride. She was a true-hearted wife and mother. The ruling motive of her professional life seems to have been not personal fame or emolument, but the unselfish desire to benefit her sex.” In addition to her medical work and suffrage advocacy, Lozier belonged to Sorosis (“Sisterhood”), an early professional women’s support network. She served as first vice president of the National Working Women’s Association, an organization that sought improved labor conditions for women of all socioeconomic classes.

Lozier’s passions came together in her defense of Hester Vaughan, an immigrant servant impregnated and then abandoned by her Philadelphia-area employer. The child died soon after birth. While no legal charges were brought against the baby’s father, Vaughan was accused on shaky ground of infanticide and sentenced to death. Feminists such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton rallied to her aid. Lozier gave Vaughan free medical care and presented exonerating medical and psychological evidence at a large public meeting organized on Vaughan’s behalf. Eventually Vaughan was pardoned and returned to her home in England.

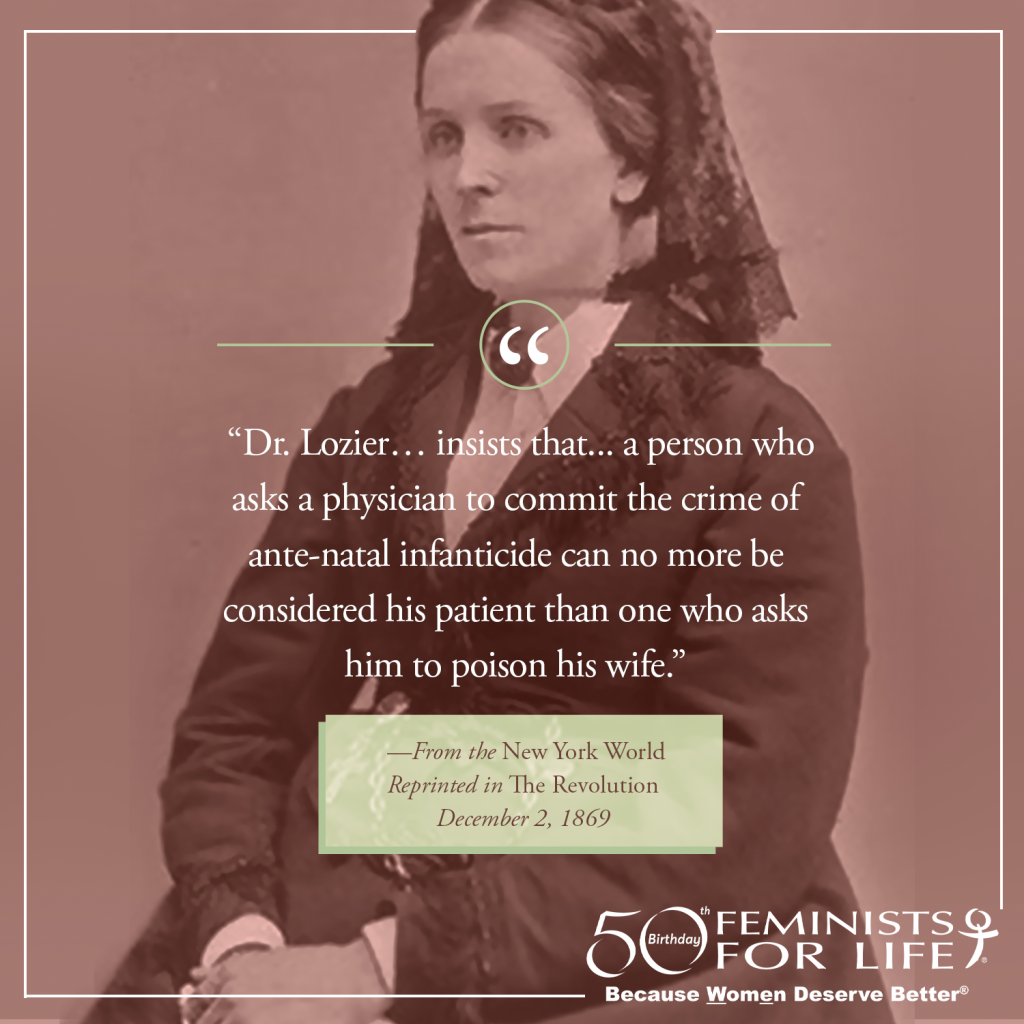

So why is Charlotte Denman Lozier’s passionate defense of women and children not recalled today? More than anything else, she was praised in her time for defending a young pregnant woman and unborn child against abortion. The patient, Caroline Fuller, had come to Lozier’s office in search of a “termination” apparently at the urging of her sexual partner, an older married man named Andrew Moran. Lozier counseled against this course of action, while kindly offering her services to help Fuller bear the child. Moran grew irate and abusive, especially after Lozier refused the large bribe he offered her to carry out his wishes. She sent for a policeman and had Moran arrested. Lozier was criticized for violating privacy. But the radical feminists press cheered her for “shielding her sex from the foulest wrong committed against it” and for “coming out firmly to stay the prevalent sin of infanticide.”

It is possible that Lozier’s empathy for Caroline Fuller and the unborn was heightened by the fact that she was pregnant at the time. Just weeks later, Lozier, only 25 years old, died in childbirth. Her untimely and widely mourned death was not blamed on the baby, nor on the innate inferiority of the pregnant female body. It was attributed to the urgent need for advances that would not come unless the medical profession and society as a whole became more sensitive to women.

As much as Lozier was missed, her death was not cited as an argument for abortion. On the contrary her anti-abortion work was seen as the crowning accomplishment of a thoroughly woman-affirming and life-affirming career. Abolitionist Paulina Wright Davis, a pioneering women’s health educator and co-editor of Stanton and Anthony’s newspaper, The Revolution, termed Lozier’s compassion toward Fuller the very action by which “we knew the woman in all her greatness.”

Why can this not be the action by which today’s feminists know Charlotte Denman Lozier “in all her greatness”? We must carry on Lozier’s unfinished struggle against a culture that still dishonors women’s strengths and gifts in the realm of reproduction and everywhere else.

Mary Krane Derr

Reprinted from The American Feminist, Fall 1997

Mary Krane Derr is co-editor of the anthology Pro-Life Feminism, Yesterday and Today.