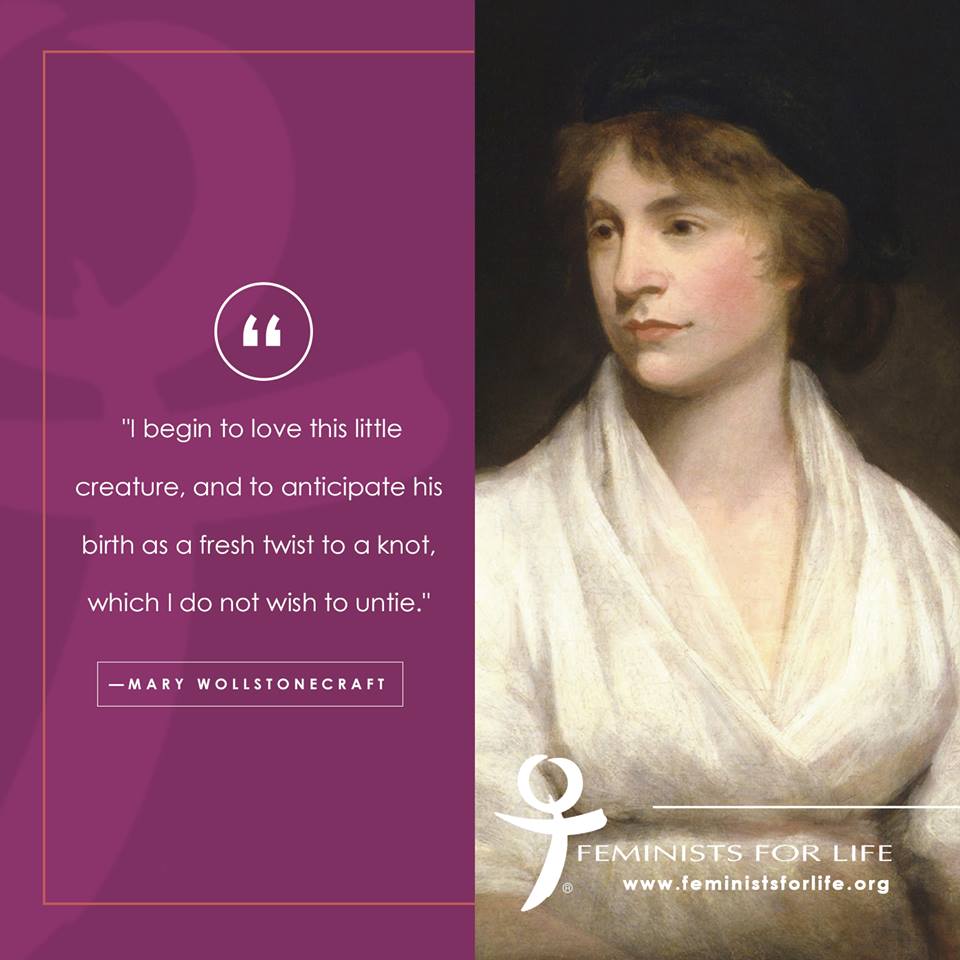

After experiencing the quickening (the first flutter of movement informing women that they were pregnant), the 18th-century pro-life feminist Mary Wollstonecraft wrote to her husband that her unborn child “took it into his head to frisk a little at being informed of your remembrance. I begin to love this little creature, and to anticipate his birth as a fresh twist to a knot, which I do not wish to untie.”

The child was actually a girl, and she was named after her mother who died shortly after giving her daughter life.

As the author of Frankenstein, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley echoed her mother’s warning in her book, The Vindication of the Rights of Woman: “Nature in everything deserves respect, and those who violate her laws seldom violate them with impunity sadržaj.”

These women called for best practices by condemning the worst….

—From FFL President Serrin M. Foster’s introduction to “Innovation: New, Revolutionary, and Best Practices.”

WOLLSTONECRAFT’S MIDDLE CLASS English family was dominated by her father’s alcoholic rages. Her mother neglected her while lavishing attention upon her brother. Despite her obviously powerful intellect, Mary was denied any education beyond the very limited, frivolous schooling that girls of her class received to become more “marketable” to prospective husbands.

Wollstonecraft, refusing the poor alternatives imposed on her, made many brave and novel decisions about her life. Following her heart rather than prescribed gender roles, she decided to support herself as a professional writer on intellectually challenging subjects — knowing full well that women who dared to assume this supposedly masculine prerogative were vilified as “unwomanly” and “unnatural.”

Wollstonecraft stood such rhetoric on its head. Her writings repeatedly assert that it is not unnatural for women to exercise their inherent rights and abilities — most of which they share with men. It is unnatural to deny women the exercise of their rights and abilities.

In her 1792 magnum opus, Vindication of the Rights of Women, Wollstonecraft clearly identifies infanticide — both pre-natal and postnatal — as an unnatural consequence of denying women’s natural rights and powers. Male sexual exploitation renders women of all social classes “weaker in mind and body than they ought to be.” Thus women “have not sufficient strength to discharge the first duty of a mother” and “either destroy the embryo in the womb, or cast it off when born. Nature in everything demands respect … men ought to maintain the women they have seduced.”

In the unfinished novel The Wrongs of Woman: Or, Maria, Wollstonecraft sympathetically offers the story of Jemima, abused and neglected as a child because of her so-called “illegitimate” birth. When Jemima becomes a house servant, her master rapes her. Discovering she is “with child,” she says: “I know not why I felt a mixed sensation of despair and tenderness, excepting that, ever called a bastard, a bastard appeared to me an object of the greatest compassion in creation.”

Concerned only to avoid his wife’s and the public’s disapproval, her master gives her an abortifacient. She refuses the “infernal potion,” as she calls it. Then the master’s wife discovers him raping Jemima again. The mistress beats and verbally abuses Jemima and throws the friendless young woman out into the street. Jemima finally obeys her master and swallows the potion “with a wish that it might destroy me, at the same time that is stopped the sensations of new-born life, which I felt with indescribable emotion.”

In her writing, Wollstonecraft drew on her personal experience of crisis pregnancy. Her lover Gilbert Imlay abandoned her and their infant daughter Fanny. Several years later, Wollstonecraft married the philosopher William Godwin, not long after conceiving their daughter Mary Godwin (later Shelley).

Mary Wollstonecraft died at age 38, after giving birth to her second daughter. Ironically, because she felt childbirth was a natural process, a male obstetrician’s overzealous, unexpected surgical intervention at a difficult point in the delivery may have caused her death.

The young Fanny was deeply scarred by her mother’s death and by her father’s abandonment. Fanny struggled with a culture unwilling to accept her mother’s vision that a life which began outside of legal marriage should be welcomed like any other. She committed suicide at 22. Her unsigned note said, “The best thing I could do was to put an end to the existence of a being whose birth was unfortunate.”

Mary Godwin Shelley, like her mother, became a radical and visionary writer, best known for her novel Frankenstein — a warning about the consequences of unbridled tampering with nature.

Source: Mary Woolstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women

Read Mary Wollstonecraft in her own words.